(Updated with additional comment from a member of the state Advisory Commission on Special Education)

(Updated with additional comment from a member of the state Advisory Commission on Special Education)

U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan is proposing to eliminate an alternative test for students with disabilities, arguing it undercuts their academic potential. The value of the test has divided the education and disability rights communities, with some advocates agreeing with Duncan and others saying the test accurately captures what students have learned.

Critics of California’s version, the California Modified Assessment, have charged that some districts have pushed administering the test to many more students with disabilities than the federal government had intended. Because students with disabilities perform far better on the modified test than on the California Standards Tests, the overall impact has been to artificially inflate districts’ and schools’ scores on the Academic Performance Index, the chief measure of student performance, concluded Doug McRae, a retired standardized testing executive who analyzed annual API results in a commentary last year for EdSource Today.

California is one of 16 states that have created a modified assessment aligned with state standards. If Duncan’s proposal is adopted, next spring will be the last year that the state can administer its modified assessment. Other states already have agreed not to offer it, as a condition for receiving a waiver from the No Child Left Behind law, according to Education Week. Duncan published his proposal last week in the Federal Register.

Duncan had pledged two years ago to do away with the test, so the announcement came as no surprise, said Deb Sigman, deputy superintendent of public instruction. The state had intended to offer students who had taken the modified assessments the same Common Core tests in math and English language arts that all students will take, starting in 2014-15. California is among the states offering the Smarter Balanced version of the Common Core tests. As a computer adaptive test, it will tailor questions to each student, based on answers to previous questions. As a result, it promises to give a more precise measure of what students have learned, she said. Sigman is on the executive committee of the multi-state Smarter Balanced consortium.

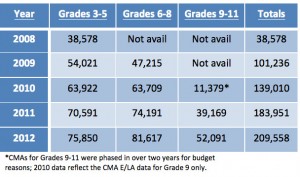

Students taking the California Modified Assessment by year and grade span. Compiled by Doug McRae (click to enlarge).

Nonetheless, Alice Parker, a Sacramento-based special education consultant and former state assistant superintendent and director of special education, said an outright elimination of a modified assessment could be harmful. For some students with disabilities, the test “closely aligned with what students were striving to learn.” Having these students take a standard test without accommodations was detrimental; the results didn’t accurately reflect the progress that many had made, she said.

At the same time, Parker agreed with McRae that districts had given the test to too many students, with the equal harm of giving “an inflated look at what students are learning.” The high scores for many students “created a false image of capability” that students discovered only when they enrolled in community colleges and universities.

Duncan’s view, shared by some advocates for the disabled, including Easter Seals and the National Center for Learning Disabilities, is that the modified assessment sells students short and, he said in a statement, “prevents these students from reaching their full potential, and prevents our country from benefiting from that potential.”

Maureen Burness, a retired director of regional special education programs and a member of the state’s Advisory Commission on Special Education, agrees. She wrote in an email “that WITH appropriate modifications in instruction and assessments, this could be the push from which most students with disabilities could benefit.” Since most special education students have learning or specific language impairments, “most should be able to learn to standards and be assessed as such.”

Since 2005, the federal Department of Education permitted states to create modified tests for special education students under the so-called “2 percent rule.” The tests were to be given to up to 2 percent of students in a district – or about 20 percent of students with disabilities. In California, only those students with disabilities who had scored below basic or far below basic on the California Standards Tests the year before were eligible for the modified assessment.

But as the California Modified Assessment was phased in, districts quickly expanded its use. Last year, 46 percent of students with disabilities in the state took the assessment, with over 50 percent in middle school. In San Bernardino, Fresno and Santa Ana unified districts and in Sweetwater High School District, more than 70 percent of students with disabilities took it. By McRae’s calculations, 39 percent of the gain in statewide API scores in elementary school and 27 percent of middle school gains over the past five years were attributable to the overuse of the test.

McRae, in an email, said that the modified assessment serves a valid purpose and he would favor creating a version aligned to the Common Core standards and restricted to 20 percent of students with disabilities. In calculating API scores, the results on a modified assessment should be discounted to take into account an easier test, which California did not do, he wrote.

California and other states also offer a separate test for the 1 percent of students with the most severe cognitive disabilities. That test, the California Alternative Performance Assessment or CAPA, was not affected by Duncan’s proposal.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Comments (13)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

navigio 11 years ago11 years ago

This was said in other ways by other commenters, but imho, this change is not about helping kids, its about closing a loophole. Period.

In the old days, a limit on CMA results that counted toward AYP was probably an actual deterrent, but now that everyone is in PI, it no longer is. In addition, API–where the CMA can still be used to a district’s advantage–is clearly more important than AYP at this point.

Replies

Manuel 11 years ago11 years ago

But, navigio, isn’t this nothing else than rearranging lawn furniture?

Closing a loophole on a test that satisfies Grand Poobahs at the ED has no real consequences to the kids, as Paul remarks. The only consequence is to the schools/districts and, it seems to me, just extends the dishonesty, in my view, that surrounds standardized testing as it relates to “academic achievement.”

navigio 11 years ago11 years ago

Since the feds have no legal role in public education, they have to work within their own, closed system. Their punitive leverage they held as blackmail in exchange for federal dollars has lost its power due to the NCLB time bomb. Thats the only reason this move is happening now. Its simply trying to regain some of that leverage. States and districts know its dishonest. But they'd rather have the money and pretend its not, … Read More

Since the feds have no legal role in public education, they have to work within their own, closed system. Their punitive leverage they held as blackmail in exchange for federal dollars has lost its power due to the NCLB time bomb. Thats the only reason this move is happening now. Its simply trying to regain some of that leverage. States and districts know its dishonest. But they’d rather have the money and pretend its not, than reject the money on principle. So far anyway.

navigio 11 years ago11 years ago

oh, and its more like exchanging the cushions on two of those lawn chairs than moving them…

el 11 years ago11 years ago

If you talk to parents of many of these students, it does matter to them quite a bit. Obviously it depends on the kid and their disability but no one likes to sit and take a test that they don't feel successful at. Doing so can really rattle your confidence. There is an assumption that the measurement is neutral but in some cases the measurement itself causes harm to the student. Many parents would choose … Read More

If you talk to parents of many of these students, it does matter to them quite a bit. Obviously it depends on the kid and their disability but no one likes to sit and take a test that they don’t feel successful at. Doing so can really rattle your confidence. There is an assumption that the measurement is neutral but in some cases the measurement itself causes harm to the student. Many parents would choose that their IEP exempt the child from standardized testing.

I am not at all an expert at IEP and special ed issues. But my sense is that there is such a range of disabilities and skill levels that the idea that any one (or two) test can tell you whether a school is properly applying the best possible effort to their special ed kids is absurd. Some of these kids are deaf and some of these kids have traumatic brain injury and some of them are severely autistic. The natural ability of these kids will vary; what sort of testing is appropriate will vary. The idea that you’re going to take a severely autistic child and administer one of these exams and then use it to fire his teacher or take funds away from his school is one of the most horrific ideas going around education “reform” right now.

Duncan is mad because he thinks schools are gaming the system. In this, he has missed the point, because … *whether the schools are gaming the system is irrelevant* to our important outcome – are these kids getting the full measure of appropriate effort from their school system? Whether this is so is orthogonal to the variable of whether the schools also game the system.

The better question to ask is: are these kids getting better outcomes, and if so, is it because of testing? And that’s a very specific and different question to ask for this particular subgroup population.

If the feds think that the wrong kids are getting alternate assessments, I’m certain they could fund independent resource coordinators to oversee special ed and to help make those decisions. Or, they could also entertain the idea of fully funding special ed.

navigio 11 years ago11 years ago

Are these tests somehow more meaningful for special education students than CSTs are to general education students? If the measurement itself were harming the student, it seems the IEP committee, and especially the parents, should choose to abstain from the test altogether. The only reason I could see those people not wanting that to happen is perhaps they consider this test as the only valid measure of the student’s progress.

Ze'ev Wurman 11 years ago11 years ago

Paul, I agree with what I think are your intentions, but you seem to be jumping in with your boots on into an area that you may want to tread softly. First, you state quite unequivocally that the 20% of SWD (or 2% overall) limit is "arbitrary." You may want to read the following report first. One can argue with some details of its findings but, whatever else, one cannot argue with a straight face that the … Read More

Paul,

I agree with what I think are your intentions, but you seem to be jumping in with your boots on into an area that you may want to tread softly.

First, you state quite unequivocally that the 20% of SWD (or 2% overall) limit is “arbitrary.” You may want to read the following report first. One can argue with some details of its findings but, whatever else, one cannot argue with a straight face that the limit was “arbitrary.”

http://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/disadv/nclb-disab/nclb-disab.pdf

Putting a limit on number of takers was intended to prevent misuse, recognizing that districts and states have an incentive to abuse them while trying to inflate their AYP — as California (and Virginia, and a few other states) did. Replacing it with “clear criteria” sounds nice but tends not to work in reality — it is much easier to manipulate the criteria (and reinterpret “clarity” 🙂 when there is a benefit to gaming them and no push-back present in the system. The 2% was a “soft” push-back in the sense that each district had the latitude to administer to more than 2% — as many did — except that beyond certain threshold the scores stopped counting towards AYP. I am not against suggesting some better combination of flexibility and control but just setting “clear criteria” ain’t going to cut it. It’s an invitation to abuse. Been there, done that.

As to parents having a say, I believe that they already do and this issue is — or at least should be — discussed during IEP meetings. But your argument that standardized scores should be considered in the light of student’s aspirations is somewhat problematic. If you mean it in the sense of not pushing for more than the student & parents want (e.g., at IEP meeting), it makes sense. If you mean it in the sense the colleges should interpret standardized achievement scores in terms of student’s aspirations … we may as well hand out college degrees together with birth certificates. It’s cheaper this way 🙂

Replies

Paul 11 years ago11 years ago

Hi, Doug and Ze'ev. I appreciate the references and the sensitivity you've expressed toward students with disabilities. I looked at the references. "Historically, the students eligible for alternate assessments have represented less than 1 percent of the total population assessed in state assessments" and "the best available research and data indicate that 2 percent of students assessed, or approximately 20 percent of students with disabilities, is a reasonable and sufficient cap" seem to be talking about statewide … Read More

Hi, Doug and Ze’ev.

I appreciate the references and the sensitivity you’ve expressed toward students with disabilities.

I looked at the references. “Historically, the students eligible for alternate assessments have represented less than 1 percent of the total population assessed in state assessments” and “the best available research and data indicate that 2 percent of students assessed, or approximately 20 percent of students with disabilities, is a reasonable and sufficient cap” seem to be talking about statewide or even nationwide student populations. I didn’t see any assertion that students with severe disabilities are distributed evenly within, let alone across, school districts. (The potential for variation becomes even larger with charter schools.) Why apply percentage limits at the district level, then?

I’m glad we agree on the primacy of the IEP.

As for colleges and universities, community colleges have open enrollment and have never been interested in scores on CDE-sponsored high school tests like the CST. Universities request the SAT or ACT, not CDE-sponsored tests. With the exception of the CAHSEE, necessary for a high school diploma (temporary exemption for students with disabilities notwithstanding), the CDE-sponsored tests have no bearing a student’s access to post-secondary education.

Doug McRae 11 years ago11 years ago

Paul: Nobody has ever said we have to apply a 20 percent limit for modified tests at the district or school level. There are many districts/schools that have heavy Spec Educ programs that constitute much higher than the average 10 percent of total enrollment, for instance county specialty schools. It would be totally unreasonable to have a blanket 20 percent limit on CMA tests for all schools and districts. But, with good guidance for who … Read More

Paul: Nobody has ever said we have to apply a 20 percent limit for modified tests at the district or school level. There are many districts/schools that have heavy Spec Educ programs that constitute much higher than the average 10 percent of total enrollment, for instance county specialty schools. It would be totally unreasonable to have a blanket 20 percent limit on CMA tests for all schools and districts. But, with good guidance for who should take CMAs and who should take CSTs, the overall participation should come out in the 20 percent range. The same situation exists for our CAPA tests, where the target is 1 percent of total enrollment or about 10 percent of Spec Educ enrollment statewide. California has been very close to the CAPA target every year since the inception of the CAPA program, and there are no district/school CAPA targets. We can attribute this to the state guidance for who takes CAPA and who doesn’t take CAPA. The same can apply to the CMA program.

Paul 11 years ago11 years ago

I don't understand, Doug. The article flags the San Bernardino, Fresno and Santa Ana school districts for heavy use of alternative assessments. Why would this be a concern if there were no limit, express or implied, at the district level? Either way, it makes no sense to reason about the percentage of students using alternative assessments in a particular district unless we also know the prevalence of specific disabilities in the district. This is the sense … Read More

I don’t understand, Doug. The article flags the San Bernardino, Fresno and Santa Ana school districts for heavy use of alternative assessments. Why would this be a concern if there were no limit, express or implied, at the district level?

Either way, it makes no sense to reason about the percentage of students using alternative assessments in a particular district unless we also know the prevalence of specific disabilities in the district. This is the sense in which the exercise is arbitrary, just like sorting students into RTI2 tiers (‘stop when you’ve filled up THIS tier with 10% of the student body’).

This is a serious concern for me because CDE-sponsored tests (other than the CAHSEE for students not covered by the temporary court-ordered exemption) provide no benefits for, and indeed have no effect on, individual students. The scores do not influence students’ grades, and they are not used for community college placement (community college admission is, of course, open) or for university admission.

The tests might provide benefits for the school system, if we accept school reform logic (‘since we haven’t figured out a universal recipe for school success, let’s rate the schools in hopes that this will force them to improve’).

When we’re trying to force students with disabilities to take unmodified tests because this will make school ratings more accurate, we are clearly not emphasizing the interests of individual students.

Paul 11 years ago11 years ago

Just like deciding that 10-15% of students need strategic intervention and 5-10%, intensive intervention, under the trendy Response to Instruction and Intervention (RTI2) framework, declaring that 20% of students with disabilities should have access to an alternative assessment is an arbitrary, and therefore irrational, move. Is there a taxonomy of disabilities, indicating the magnitude of each disability's effect on academic performance? Are prevalence rates for each disability consistent from school to school within a district, let … Read More

Just like deciding that 10-15% of students need strategic intervention and 5-10%, intensive intervention, under the trendy Response to Instruction and Intervention (RTI2) framework, declaring that 20% of students with disabilities should have access to an alternative assessment is an arbitrary, and therefore irrational, move.

Is there a taxonomy of disabilities, indicating the magnitude of each disability’s effect on academic performance? Are prevalence rates for each disability consistent from school to school within a district, let alone between districts? (What of charter schools?)

The decision to use an alternative assessment should be made by the student, the student’s parent or guardian, and the student’s special and regular education teachers, in consultation. The correct decision requires knowledge of the student, and is thus a little too important to be made systemically by Arnie Duncan or Dr. Doug McRae, whatever the extent of their experience actually teaching actual children in actual public school classrooms, actually within the last decade, let us say (for solid experience with special education inclusion).

I favor outlining clear criteria for use of alternative assessments, not limiting access to some arbitrary percentage of students. The former approach serves students, whereas the latter serves adults whose overriding concern is the accuracy of the state’s school ranking algorithm.

Special education students who struggle in community college or university struggle due to the severity of their disabilities or to the insufficiency of chosen/available accommodations and modifications. Which test was taken in high school is not a factor. Students and families rarely treat any of the state’s standardized tests as evidence of personal “capability”. At the individual level, standardized test scores must be considered in the light of teacher-assigned grades and — more importantly — student aspirations. For a special education student, this last item has a very particular meaning: goals written into the student’s IEP.

Replies

el 11 years ago11 years ago

Bravo, Paul. I wish Duncan wanted to spend more time with his family. Barring that, perhaps he should spend a few months teaching profoundly disabled children. The modified test is a one-size-fits-all answer to thousands of questions, kids with a variety of disabilities and impairments. To suggest that if only they'd taken an exam with 5 answer choices instead of 3 they'd be successful in college requires a level of vapidity that is profoundly disappointing in … Read More

Bravo, Paul. I wish Duncan wanted to spend more time with his family. Barring that, perhaps he should spend a few months teaching profoundly disabled children.

The modified test is a one-size-fits-all answer to thousands of questions, kids with a variety of disabilities and impairments. To suggest that if only they’d taken an exam with 5 answer choices instead of 3 they’d be successful in college requires a level of vapidity that is profoundly disappointing in our Secretary of Education. Perhaps Duncan would be smarter if he started every day by taking a standardized test.

Doug McRae 11 years ago11 years ago

Paul: The decision by ED in DC back in 2005 to allow for modified tests for 20 percent of the Spec Educ population was a judgment call, but far from arbitrary. It was research data from neuroscientists who studied differing Spec Educ disabilities and concluded that 70 percent of Spec Educ students should be able to take the same tests as all non-Spec Educ students take -- and with 10 percent of the most … Read More

Paul: The decision by ED in DC back in 2005 to allow for modified tests for 20 percent of the Spec Educ population was a judgment call, but far from arbitrary. It was research data from neuroscientists who studied differing Spec Educ disabilities and concluded that 70 percent of Spec Educ students should be able to take the same tests as all non-Spec Educ students take — and with 10 percent of the most severely cognitive challenged students already taking the CAPA-type tests across the country, that left 20 percent in need of a “modified” test. I believe that research rationale still stands. Alice Parker, who was quoted in the post, knows a lot more than I do about how the 20 percent in need of modified tests should be be identified; we need Spec Educ expertise on that element of this issue. But, I would very much agree with you the IEP team is central for individual student decisions. It should be a matter of getting the right information to IEP teams on which students need to take a CMA version and which students need to take a CST version of STAR — that’s the primary flaw in the way that CA implemented the CMA program from 2008 thru 2011.