Gov. Jerry Brown has proposed an unfamiliar budget for public education in the state – one with actual increases. His 2013-14 spending plan for K-12 schools includes a revision of his plan to reform the state’s convoluted, inequitable school finance system that lawmakers and a coalition of education groups rejected last year. Passing it would be a priority, Brown said.

Brown wants to increase overall spending for K-12 and community colleges in the 2013-14 fiscal year by 5 percent: $2.7 billion, which translates to $337 per student. Total spending would rise to $56.2 billion next year.

Brown said at a news conference Thursday that passing education finance reform would be a priority.

That growth in revenue, guaranteed by Proposition 98, together with extra money from the passage of Proposition 30 in November, would be split between continuing to pay off late payments to schools – part of the state’s “wall of debt” that Brown is determined to shrink rapidly – and phasing in a new funding system that would steer more money to low-income students, English learners and a new group: foster-care children.

Brown also wants to shift the responsibility for adult education from K-12 districts to community colleges, with an extra $300 million given to community colleges for that purpose, and to dedicate $450 million in new revenue to school districts and community colleges for energy efficiency projects.

Phase in finance reform

Brown’s finance reforms would direct additional funds to school districts based on their enrollments of English learners and low-income students. The new K-12 finance system, now christened the “local control funding” formula, is similar in major respects to the “weighted student funding” formula that lawmakers shunted aside last year. But since then voters passed Proposition 30, providing more than $2 billion annually to Proposition 98, with forecasts of an economic bounce-back.

Brown administration officials also say they are incorporating some of the criticisms from meetings with district officials and student advocacy groups in November. “Gubernatorial leadership, a better proposal, a better fiscal situation and a communication campaign” where none existed last year convinced State Board of Education President Michael Kirst that this may truly be the year of reform. “A policy window has opened,” said Kirst, who co-wrote the original plan for a weighted formula five years ago.

The goal is a simpler, clearer and more uniform way to fund schools. By eliminating nearly all of the remaining state programs with spending restrictions, called “categoricals,” the new plan would continue the process of transferring power from Sacramento – aka passing the buck – that started four years ago when lawmakers slashed district budgets. Now, Brown wants to make permanent what he calls the “principle of subsidiarity” – giving more authority to those closer to the classroom.

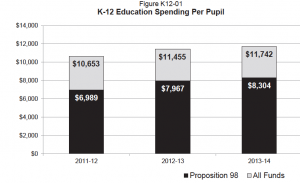

Total K-12 spending per student from all sources would be $11,742 next year. Proposition 98 spending would be $8,304 per student, an increase of $337 from this year and $1,315 from two years ago. Source: proposed 2013-14 state budget, page 25 (click to enlarge).

The ultimate authority for spending decisions would be the district office, not the schools, and supplementary dollars would be allocated on the numbers of students in need per district. In a press conference, Brown acknowledged that a new finance system might not please districts that have fared relatively well under quirky, inequitable funding formulas or that educate fewer of the targeted groups of children.

But, quoting Aristotle, he said, “Treating unequals equally is not justice.” The resource needs of students in Compton are not the same as those in Santa Monica, he said, and it is not right, fair and just to fund them similarly. “Suburbanites who can see over the horizon” have an interest in seeing that inequalities are eliminated, he said.

Brown and administration officials reiterated that all districts would be fully repaid money that the state has cut and borrowed from them.

- Deferrals: For five years, the state has been paying districts increasing amounts of money a year late. Last year, the total was $10.4 billion – about 20 percent of the Proposition 98 obligation due them. This forced districts to borrow money, adding expense and creating cash flow problems. This year, the state is repaying $2.2 billion. Brown proposes to pay off an additional $1.8 billion next year and to wipe out the deferrals by 2017-18.

- Budget cuts: Within seven years, when the new funding formulas are fully phased in, Brown is promising to repay districts the 20 percent of the base spending lost since 2008-09 through foregone cost-of-living increases and budget cuts. Districts would be repaid at different rates. Those that receive the least money now, compared with what they would receive under the new formula, would be get more money faster.

As for the Local Community Funding Formula, details and district-by-district allocations, enabling districts to compare how they’d fare under the new system versus the status quo, won’t be available for weeks. However, the budget summary offered highlights and Brown officials added some details in interviews and in a press conference.

Districts currently receive a combination of an unrestricted grant, called the revenue limit, plus categorical grants. Both vary from district to district. Some outdated formulas go back 30 years; others have been frozen and have failed to keep up with student growth and declines.

Under the new formula, districts will receive a base grant plus supplemental dollars based on the number of students who are English learners, in foster care or whose families are low-income. The following figures are preliminary – and will change, as the formula is revised. (It may have already been revised by the time you read this.)

Base grant: It will be equal to the fully repaid revenue limit. Currently, with cuts it’s about $5,500; the target is an average of $6,800 in seven years, according to Nicolas Schweizer of the state Department of Finance. Grades K-3 will continue getting additional money for reducing class sizes but, for now, districts can spend the money as they choose. The same flexibility will apply to career technical education categorical grants, which will be folded into the basic per-student grant for high school grades.

While superintendents have been clamoring for more flexibility, defenders of technical education and Partnership Academies, which prepare students for college and careers, worry that districts might cut funding for the programs. Until the state accountability system is changed, districts will overvalue subjects, like English language arts and math, that are tested, said Fred Jones, who represents a coalition of employers, labor groups and others concerned about career technical education. “The only real assurance we have under the current confines that CTE dollars will be spent on career prep is for those dollars to be limited only to bona fide career prep programs and expenses.”

Supplement dollars: Every low-income and foster care student and students not proficient in English will get an extra 35 percent of the base grant: $2,380, once fully phased in. So, for example, for a district where 25 percent of students are targeted for extra funding, the average per-student funding in seven years would be $7,395 ($6,800 base plus $595 supplement). A district with 50 percent students in need would get $7,990 ($6,800 plus $1,190).

Last year, in the May revision of the budget, Brown was recommending only an extra 20 percent of the base grant.

Concentration factor: Districts where low-income and other students in need comprise over half of the student body will get even more bonus money on top of the supplement, based on the assumption that concentrations of low-income students and English learners pose extra challenges. (Some superintendents and policy advocates dispute this assertion.) This will also be 35 percent. So a district with 75 percent students in need would receive $9,180 per student ($6,800 plus $1,785 supplement plus $595 concentration bonus).

Categorical programs: Districts will continue to receive more than $1 billion in categorical dollars for bus transportation and Target Instruction Improvement Grants, but the amounts will be frozen. Continuing TIIG – once allocated for desegregation programs but now general dollars – is a particular nod to Los Angeles Unified, the biggest beneficiary by far, which has built this money into its current budget for decades.

The new funding system retains separate funding for special education and nutrition programs and after-school programs funded under Proposition 49, which together total about $4 billion.

Accountability: Last year some advocates for low-income students and English learners had criticized Brown’s plan to allocate money to districts rather than to individual schools out of concern that extra dollars might not be spent on those students.

Money will continue to be distributed to a school district’s central office, but Brown would require a District Plan for Student Achievement, in which districts must annually account for how money would be spent on low-income students and English-language learners and document that all students have qualified teachers and sufficient materials. For the first time, districts would also have to demonstrate how they implement Common Core standards and progress made toward career- and college-readiness goals.

Sue Burr, Brown’s chief education adviser, said that the state would not withhold money from districts that are out of compliance. The assumption is that parents and advocacy groups would hold administrators and school board members accountable for how funds are spent. Among the children’s advocates who praised the concept of weighted funding Thursday while cautioning that they need more information was John Affeldt, managing partner at Public Advocates, a nonprofit law firm. “We remain enthusiastic supporters of the concept of spending more on kids who need more resources to get to the same level of achievement,” he said. The requirement for a district accountability plan is “a concept that we and other advocates had pushed for and is a step in the right direction, but we await details.”

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Comments (7)

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.

el 11 years ago11 years ago

I am pleased to see that Career Technical Education money did not get forgotten in this go round. Locally, I see relatively strong support for those programs, but the previous proposal had (accidentally?) eliminated that funding which would have made it very difficult to keep the programs. Perhaps more urban districts would see more pressure to put that money into more traditionally academic subjects than we do.

Replies

Chris 11 years ago11 years ago

Great that the Gov. included some funding for CTE but do many realize that those dollars are also “Flex” and can be used by districts anyway that want? We all know how that goes.

The ROC/Ps that have been the successfully delivery system for CTE over 45 years are completely eliminated as part of the Gov.’s budget proposal.

John Fensterwald 11 years ago11 years ago

Paul: I doubt whether the state will want to get involved in monitoring how the money for English learners is used at a district or school level, BUT the governor is proposing a 5-year limit in money for ELs, in order to counter the financial disincentives of moving students to English proficiency. This would represent a major change, as you know. Keep in mind that students will get one amount -- an extra 35 percent -- … Read More

Paul: I doubt whether the state will want to get involved in monitoring how the money for English learners is used at a district or school level, BUT the governor is proposing a 5-year limit in money for ELs, in order to counter the financial disincentives of moving students to English proficiency. This would represent a major change, as you know.

Keep in mind that students will get one amount — an extra 35 percent — whether they are EL or low-income; student who are both don’t get double money. However, most English learners are from low-income families and so would continue to qualify for supplemental money after 5 years.

Replies

el 11 years ago11 years ago

One of the realities of EL and low income kids is that if they were ever classified that way, they will probably always need more support. For example, it's unlikely that they have a parent who attended college, which means they would benefit from more counseling support. If we have enough money to provide an adequate level of counseling support to all students, this may not matter, but in the resource limited environment we've experienced … Read More

One of the realities of EL and low income kids is that if they were ever classified that way, they will probably always need more support. For example, it’s unlikely that they have a parent who attended college, which means they would benefit from more counseling support. If we have enough money to provide an adequate level of counseling support to all students, this may not matter, but in the resource limited environment we’ve experienced lately, it’s much more apparent.

Paul 11 years ago11 years ago

I will add that last year's and this year's weighted student funding proposals are significant in that they contradict the naive assumption on which the state's anti-tax provisions rest: that population growth and general inflation are the only determinants of growth in state spending. That we have services for English Learners today proves that the scope of government service may increase as a result of societal changes. In a similar vein, accommodating low-income earners recognizes … Read More

I will add that last year’s and this year’s weighted student funding proposals are significant in that they contradict the naive assumption on which the state’s anti-tax provisions rest: that population growth and general inflation are the only determinants of growth in state spending. That we have services for English Learners today proves that the scope of government service may increase as a result of societal changes. In a similar vein, accommodating low-income earners recognizes that a weak economy can increase the demand for government services.

Paul 11 years ago11 years ago

I wonder whether income questionnaires, CELDT tests, and RFEP decision inputs will be audited by the state, or whether the low-income and English Learner categories will be abused, in the same way that the free or reduced-price lunch program has turned into a free-for-all. Short of audits on parents (for income) and districts (for CELDT results), one way to prevent abuse would be to legislate a trajectory, i.e., to clamp a district's year-over-year increases in supplemental … Read More

I wonder whether income questionnaires, CELDT tests, and RFEP decision inputs will be audited by the state, or whether the low-income and English Learner categories will be abused, in the same way that the free or reduced-price lunch program has turned into a free-for-all.

Short of audits on parents (for income) and districts (for CELDT results), one way to prevent abuse would be to legislate a trajectory, i.e., to clamp a district’s year-over-year increases in supplemental and concentration funding.

Except in high-growth areas, of which there are few in California, there should not be substantial increases in the English Learner population from year to year. The low-income population, for its part, will vary everywhere, with the overall economy.

In gentrifying areas, such as San Francisco, the number of English Learners and the number of low-income students will decline over time. It will be interesting to see whether districts admit such declines or try to hide them, holding on to the extra money.

Replies

ssy 11 years ago11 years ago

Paul - what do you mean by "free or reduced-price lunch program has turned into a free-for-all"? In my observation of our school district's budget document, the reported number of SES and EL student is quite high for our area, much higher than you would expect based on census data, and based on the median income/housing prices of our area. My hunch is that there is some sort of numbers game going on, … Read More

Paul – what do you mean by “free or reduced-price lunch program has turned into a free-for-all”? In my observation of our school district’s budget document, the reported number of SES and EL student is quite high for our area, much higher than you would expect based on census data, and based on the median income/housing prices of our area. My hunch is that there is some sort of numbers game going on, just enough to not cause alarm but a very conveniently nice number, but this is first time coming across someone saying the same thing. Can you enlighten me?